[1] CHILD WELFARE AND JUVENILE JUSTICE: Federal Agencies Could Play a Stronger Role in Helping States Reduce the Number of Children Placed Solely to Obtain Mental Health Services (GAO-13-397, April 21, 2003). http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d03397.pdf. Estimate based on national survey conducted in 2001. See, generally, “Staying Together: Preventing Custody Relinquishment for Children’s Access to Mental Health Services,” Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law and Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health (1999) and “Relinquishing Custody: The Tragic Result of Failure to Meet Children’s Mental Health Needs,” Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law (2000), both available from Bazelon. PDF version of 1999 publication available at http://www.bazelon.org/.

[2] As of 2003, eleven states permitted access to child welfare services without loss of custody, and six states plus the District of Columbia forbade voluntary provision of child welfare services altogether. The remaining states had no clear policy on custody relinquishment. Id. This list has not been updated by the GAO or Bazelon nor is more recent information available from the National Conference of State Legislatures. Many states have acted since then, but state performance depends on the appropriations process as well as substantive law, so the extent of the problem is difficult to quantify. A 2010 Colorado statute takes the bold step of creating a state-funded safety net for children’s mental health services, using the separate household approach:

Colo. Rev. Stat. 27-67-104. Provision of mental health treatment services for youth (1) (a) A parent or guardian may apply to a mental health agency on behalf of his or her minor child for mental health treatment services for the child pursuant to this section, whether the child is categorically eligible for medicaid under the capitated mental health system described insection 25.5-5-411, C.R.S., or whether the parent believes his or her child is a child at risk of out-of-home placement. In such circumstances, it shall be the responsibility of the mental health agency to evaluate the child and to clinically assess the child’s need for mental health services and, when warranted, to provide treatment services as necessary and in the best interests of the child and the child’s family. Subject to available state appropriations, the mental health agency shall be responsible for the provision of the treatment services and care management, including any in-home family mental health treatment, other family preservation services, residential treatment, or any post-residential follow-up services that may be appropriate for the child’s or family’s needs. For the purposes of this section, the term “care management” includes, but is not limited to, consideration of the continuity of care and array of services necessary for appropriately treating the child and the decision-making authority regarding a child’s placement in and discharge from mental health services. A dependency or neglect action pursuant to article 3 of title 19, C.R.S., shall not be required in order to allow a family access to residential mental health treatment services for a child.

[3] A 2006 Virginia Attorney General’s opinion ruled that §2.-5211(B)(3) of the Virginia Comprehensive Services Act (CSA) requires the state and localities to serve children who are at risk of foster care placement without requiring their parents to relinquish custody. In Missouri, under SB 1003 (2004), Section 630.097, RSMo established a comprehensive children’s mental health service system to serve children in the least restrictive environment. http://www.senate.mo.gov/04info/billtext/tat/sb1003.htm This legislation has effectively ended custody relinquishment in MO.

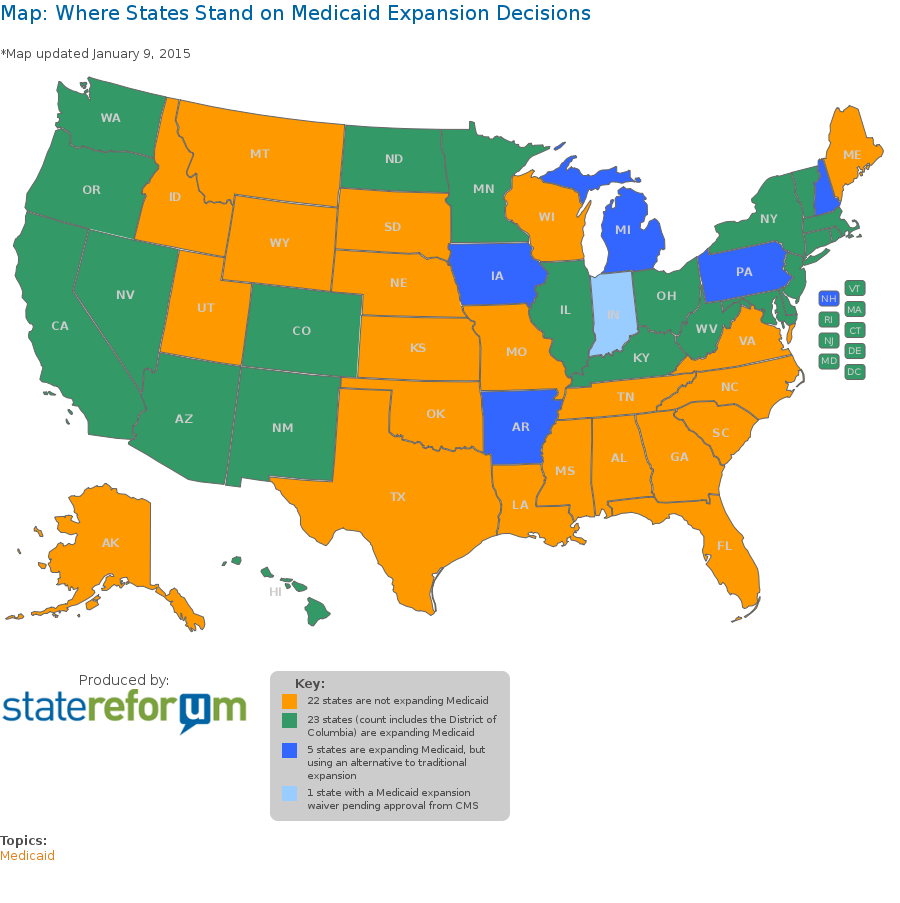

[4] In Colorado, a one million dollar state general fund subsidy is still required, despite full Medicaid expansion and a robust CHIP program. In contrast, in California, the 2005 Proposition 63 ballot measure included language providing that if access to mental health care was the cause of relinquishment and there was no other funding source to pay for it, counties could provide Prop 63 funds to a family to pay for the care. This has been in the law for 10 years, but no one has used it, in part because CA also has a title IV -E waiver under federal child welfare laws for wrap around in-home care as an alternative to out of home placement for kids with serious emotional disturbance. But this is a bad solution since technically the family has given up custody in those cases even though the child remains at home. This is a very widely used approach.

[5] States need to develop their children’s mental health service system with funding that allows for flexibility beyond the constraints of Medicaid rather than disrupting families to fit into the constraints of a particular funding stream. This should include state funds to cover non-Medicaid-eligible children and maximizing funding from available commercial insurance coverage, then supplementing it with state funds to fill the gap. Often, public mental health programs are not designed in a way to accept private insurance payment or even to accept private payment from the family. This is because the entire public community mental health system has been designed with the goal of obtaining maximum Medicaid funding.

[6] See Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius (NFIB), 132 S. U.S. 2566 (2012), http://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/11-393

[7] Texas, the only state for which coded data was obtained, documented that in 2008, in three of 788 cases of child welfare funding based on “refusal to assume parental responsibility,” the underlying reason was “lack of mental health services.” As of 2014, despite an array of state initiatives to decrease reliance on custody relinquishment, Texas estimated an ongoing gap of 60 RTC beds as well as a need for more wrap-around and prevention services: “The collaborative DFPS/DSHS RTC Project has been successfully diverting parents/guardians from relinquishing custody of their children with SED to DFPS by placing children who meet RTC criteria in DSHS-funded RTC beds. However, the 20 children on the RTC waiting list at the end of September 2014 exceed the current capacity of the RTC Project, which is funded for 10 ongoing beds in fiscal year 2014-2015. To date, the project reportedly has effectively prevented the relinquishment of 61 children since the project officially launched with the first RTC placement in January 2014. It is recommended that the number of available RTC beds be increased by 20, for a total of 30 ongoing RTC beds per year. With an expected average length of stay of 6 months, about 60 children would be served per year and diverted from DFPS conservatorship.” Department of Family and Protective Services and Department of State Health Services Joint Report on Senate Bill 44December 2014).

[8] http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Achieving-the-Promise-Transforming-Mental-Health-Care-in-America-Executive-Summary/SMA03-3831

[9] P.L. 108-446 (December 3, 2004), 20 USC§1400.

[10] This information is purely anecdotal. The last known survey was the GAO survey, conducted in 2001.

[11] “Medicaid EPSDT Litigation,” produced by Jane Perkins, National Health Law Program (October 2, 2009), http://www.acmhai.org/pdf/jane_perkins_-_epsdt_litigation.pdf

[12] The other is Massachusetts.

“In general, Medicaid Buy-In programs are accessed by two groups, which are not mutually exclusive:

The first group, usually individuals with a serious mental illness or another chronic condition such as Multiple Sclerosis or AIDS, use MBI programs as secondary, or wraparound, coverage to their primary insurance, Medicare. Without the Medicaid Buy-In, these individuals would lose access to this secondary coverage for Medicare. The costs of their drug coverage and other medical services would rise. They would be forced to quit their jobs in order to maintain affordable and comprehensive Medicaid coverage for their medical conditions.

The second group uses a MBI program to access services not covered by Medicare or any type of private insurance, such as long term care services and state Medicaid waiver services, including services such as personal attendant care. These services are critical to individuals with conditions that limit their daily activities, and they will need to access them through Medicaid, with or without a Buy-In program. Medicaid Buy-In programs simply allow these individuals to work and increase their financial independence while keeping these critical medical services. Take away the Medicaid Buy-In program and Medicaid will still have to provide the services, it is just that the individuals will have to quit their jobs in order to meet the lower income limits for other Medicaid programs.

None of the new options created under the ACA will provide these individuals with the comprehensive coverage necessary for their conditions. Newly-eligible Medicaid is not available to most of them because they are Medicare beneficiaries. For those who are not, there is no guarantee that the new category of Medicaid will cover the long term care services that they may need. Private insurance policies sold through the newly developed State Insurance Exchanges will likely be unavailable or inadequate for most of them for the same reasons.”

[14] Acting Director of the Texas Youth Commission which provides mental health services to the state’s juvenile correctional system.

[15] New York Times, “Mentally Ill Offenders Strain Juvenile [Justice] System,” by Soloman Moore, August 10, 2009 ; Marvin D Feit , John S Wodarski, Catherine Dulmus , and Lisa A. Rapp-Paglicci ,Juvenile Offenders and Mental Illness :I Know Why the Caged Bird Cries (Routledge 2014).

[16] Bazelon: Litigation Strategies (out of date): http://www.bazelon.org/issues/children/custody/litigation.htm