We’re tired of the statistics, so let’s just get it out there:

AAPIs are the least of any race to seek mental health help, although we need it

AAPI individuals are the least likely of any racial group to seek help (three times less likely than white individuals), with a 17.3% overall lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorders, and yet only 8.6% seek mental health help.[1]

Thao Duong, 29, has worked in mental health most of her adult life, first at the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and then at Asian Women’s Shelter in San Francisco.

“Often it feels like because so few of us seek help, people assume that AAPI people just don’t need mental health services because we don’t reach out,” she said, “These statistics show false stories. Not only that, a lot of our research lumps us all together as if we’re one category.”

The pandemic and compounding crises have had a colossal impact on our society’s mental health this past year. 43% of AAPI respondents say COVID-19 has negatively impacted their mental health, according to a KFF survey [2]. Moreover, the rise in the number of reported acts of violence and discrimination towards the AAPI community this past year has further impacted the mental health of our communities. Within the AAPI community, a significant relationship was found between discrimination and depression and anxiety.[3] And while racism toward our community isn’t new, the pandemic and compounding crises have further illuminated the need for mental health care within the AAPI communities.

These are statistics that we, Asian Americans and healthcare professionals, have been inundated with, especially in the past year. There are many reasons as to why, but part of the reality is that we don’t have many more statistics to go off of, as one of the issues is the lack of research for the AAPI population, especially research that disaggregates data amongst the AAPI diaspora.[4]

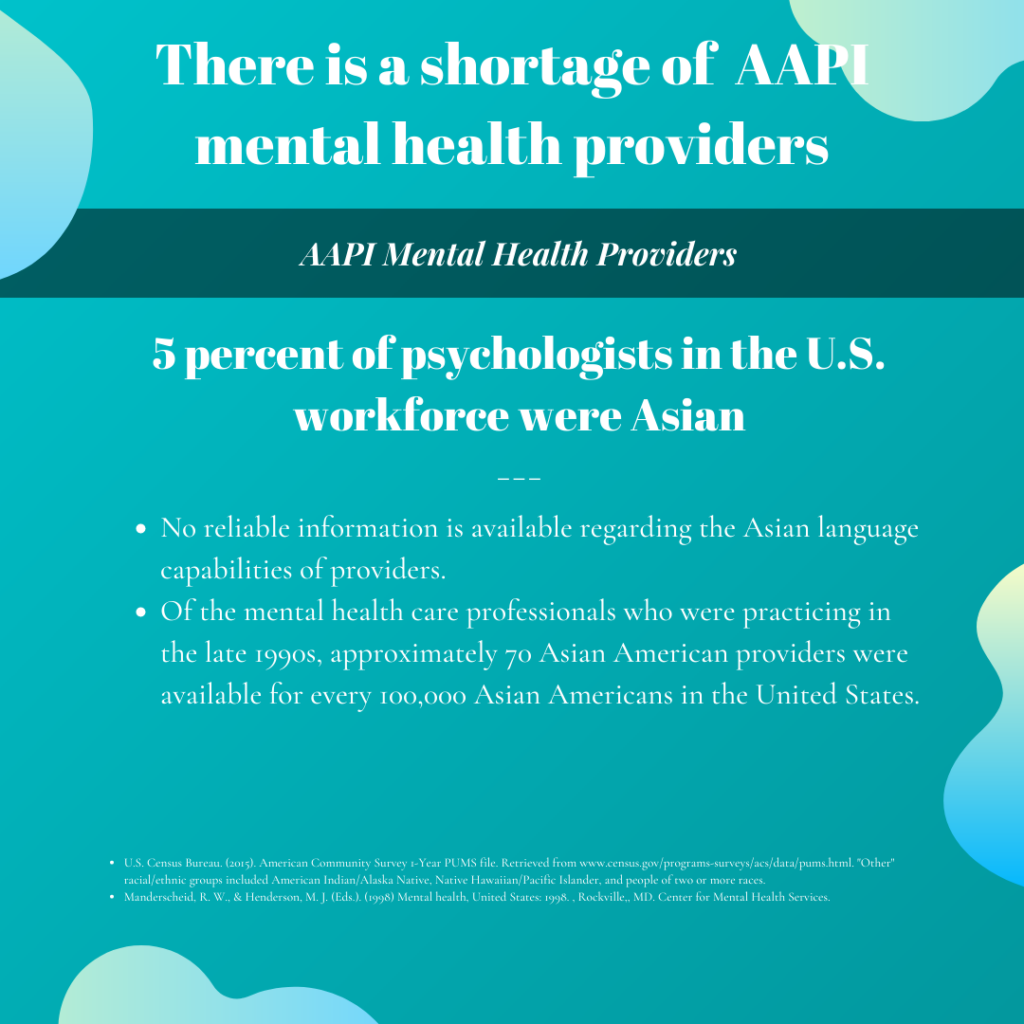

Among all the barriers, there is a lack of AAPI providers

Five percent of the psychologist workforce identifies as Asian and 1% are multiracial or from other racial groups (which included Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander), as opposed to 86% who identify as white. [5]

The demand for AAPI therapists has far surpassed the supply.

“I realized that despite my frequent recommendations for Asian Americans to seek mental health care, many would return reporting that a lot of the Asian providers were full at this time,” said Dr. Jenny Wang of @asiansformentalhealth, “We cannot expect clients to receive care if there are not enough providers to serve them.”

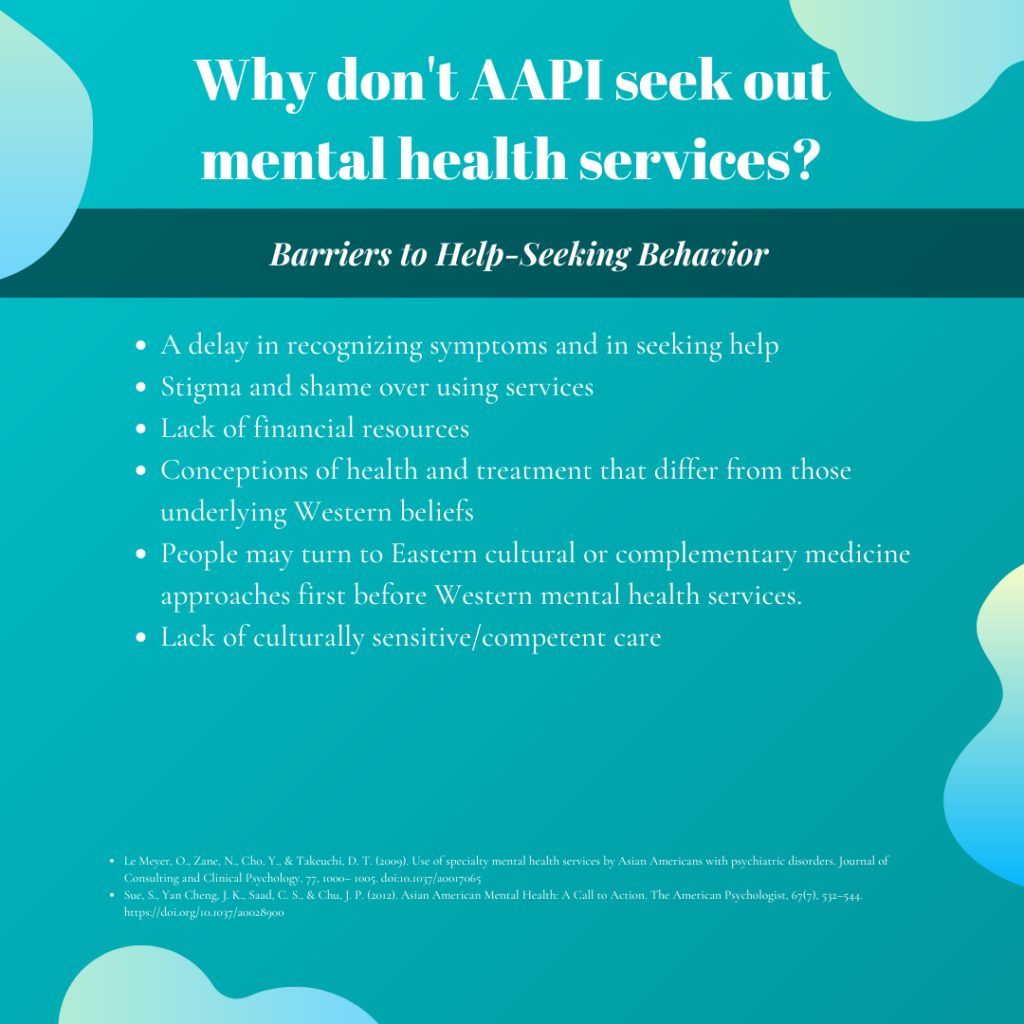

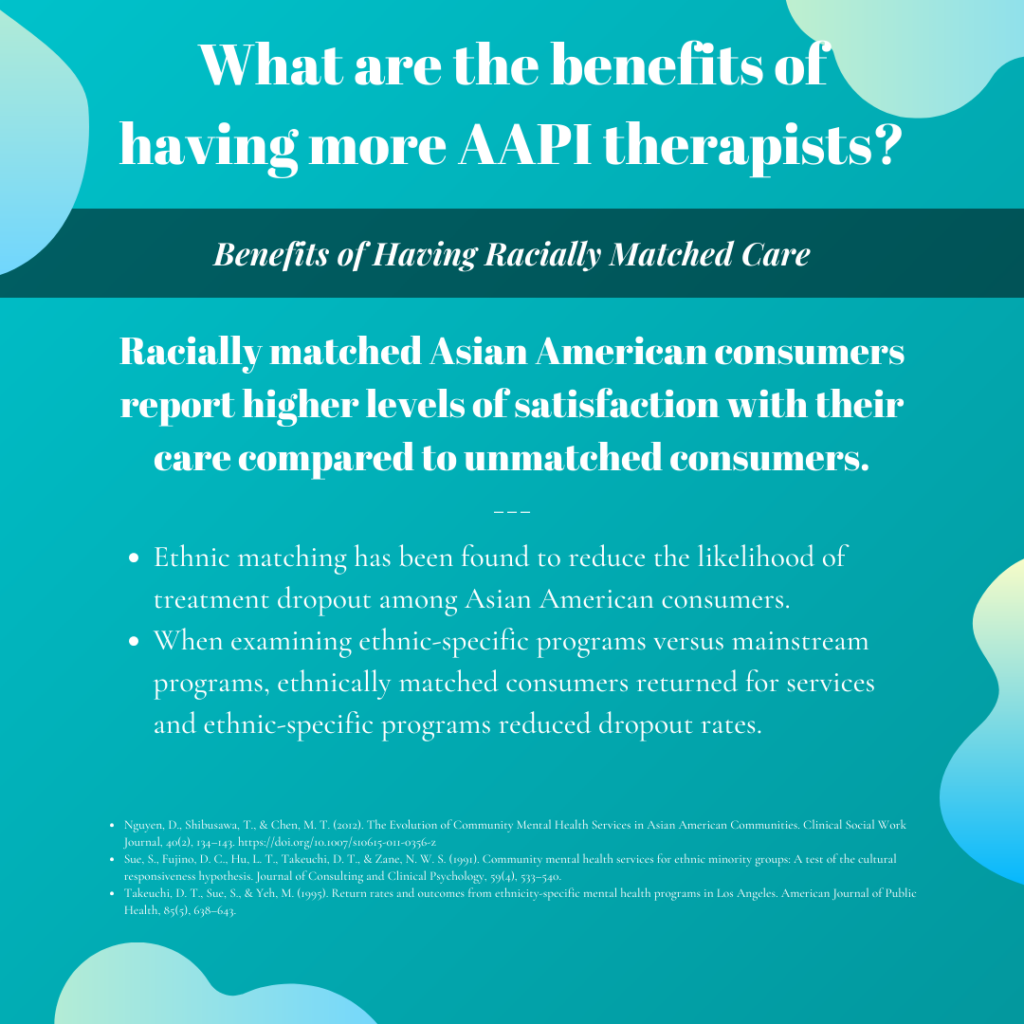

Additional barriers to seeking treatment include stigma and shame, lack of financial ability, and the lack of ethnic and linguistic-specific services, among others.[6] Asian American patients who see Asian American providers report higher satisfaction with their care, especially when they are ethnically and linguistically matched.[7]

When Duong herself sought therapy before the pandemic, she felt that while her therapist was helpful in many ways, the therapist would make comments that made it obvious her lack of understanding with AAPI and queer issues.

“She would say things like, ‘I have experienced this in my AAPI patients and I felt like I was being generalized,” said Duong.

Another time, the therapist commented casually, “where you come from in your country” (Duong was born in Fargo, North Dakota and raised in Sacramento, California).

“To this day, I still remember how that felt,” said Duong, “I’m really hoping to forget it.”

Culturally competent care is also critical to addressing specific mental health needs related to intersectionalities. Rylan Rosario, a queer Black and Guamanian doctoral candidate in counseling psychology, shared the importance of finding a clinician that you can relate to and is culturally humble.

“It’s important that they understand your culture and what that means.For example, we tend to be more collectivist but we live in a very individualistic society…so [a clinician] might say, well your family is too enmeshed, and look at that as something that’s not okay and healthy, but the reality is that’s normal for us, that’s how we get through,” Rosario said, “Sometimes if it can be a little toxic, it should be like, can we work through that? But I don’t want to change the dynamics of my family structure, we all help each other.”

“When we are talking about mental health, it is impossible to understand a person’s mental health without considering the impact of their racial and ethnic identity on how they see their world and their place in it,” said Dr. Wang, “Unfortunately the field of mental health has predominantly been a Eurocentric field up until this point and so serving the Asian American Pacific Islander community can be difficult when providers are not equipped to appreciate the cultural nuances and inter-generational facts that impact Asian Americans in their mental health.”

We need providers who understand us to improve AAPI mental health care and to further the overall mental health field

Dr. Wang and I (Elissa) are working toward developing an AAPI therapist directory to make it easier for patients to access therapists, as well as a scholarship fund to raise up the next generation of AAPI therapists. So far, we have raised $16,000 toward a goal of $30,000.

“People of color are much less likely to pursue graduate training or mental health fields due to the heavy costs associated with advanced training,” said Dr. Wang, “We hope that through the scholarship fund we are able to help alleviate some of those costs for future mental health professionals of AAPI descent.”

Having more AAPI providers in the mental health field helps to decolonize therapy and moves us toward a better understanding not only of AAPI mental health but of mental health as a whole.

Duong was able to find a therapist through Dr. Wang’s website last year at the height of the pandemic.

“With the spotlight on hate crimes toward the AAPI community, I was crying a lot and…it was so hard, I didn’t know how not to cry or how not to be anxious leaving my house,” Duong said.

She was scrolling through Instagram when she found Dr. Wang’s call for sliding scale AAPI therapists, and was able to reach out to two therapists — one for her sibling and one for her.

“It just felt nice, just for her to be from the same background, just for her to understand,” Duong said.

Graphic by Trevor San Antonio, who also contributed to this report.

Please consider donating and sharing our campaign (https://tinyurl.com/aapimentalhealthfund) and inviting all the AAPI therapists you know to join the directory at https://asiansformentalhealth.com/.

Dr. Elissa S. Lee (she/her) is a proud daughter of immigrants; she is also a sister, a grandchild, a cousin, a friend. In her attempts to improve health equity and make the world a kinder and braver place, other titles she holds include: health care journalist, chronic care researcher, occupational therapy clinician, nonprofit consultant, dancer, and amateur cook. Lee holds a doctorate from USC and a B.A. from UC Berkeley.

Dr. Elissa S. Lee (she/her) is a proud daughter of immigrants; she is also a sister, a grandchild, a cousin, a friend. In her attempts to improve health equity and make the world a kinder and braver place, other titles she holds include: health care journalist, chronic care researcher, occupational therapy clinician, nonprofit consultant, dancer, and amateur cook. Lee holds a doctorate from USC and a B.A. from UC Berkeley.

Lillian Man (she/her) is an MSW/MPH candidate at UC Berkeley. As a daughter of immigrants, she dedicates her work to improving the lives of vulnerable populations. She has worked at San Francisco Suicide Prevention, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, and Asian Health Services. Her current research is focused on the pandemic’s economic impact on AAPI populations.

Lillian Man (she/her) is an MSW/MPH candidate at UC Berkeley. As a daughter of immigrants, she dedicates her work to improving the lives of vulnerable populations. She has worked at San Francisco Suicide Prevention, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, and Asian Health Services. Her current research is focused on the pandemic’s economic impact on AAPI populations.

[1] Discrimination and Mental Health–Related Service Use in a National Study of Asian Americans: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2978178/

[2] Asian Immigrant Experiences with Racism, Immigration-Related Fears, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Asian Immigrant Experiences with Racism, Immigration-Related Fears, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

[3] Racial Discrimination and Asian Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0011000010381791

[4] Health research funding lags for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/08/190815142522.htm

[5] U.S. Census Bureau. (2015). American Community Survey 1-Year PUMS file. “Other” racial/ethnic groups included American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and people of two or more races.

[6] The Evolution of Community Mental Health Services in Asian American Communities https://link-springer-com.libproxy1.usc.edu/article/10.1007/s10615-011-0356-z

[7] Ibid.